Cutting the Gordian Knot. From Monolith to Modular

Legend tells of Alexander the Great encountering the Gordian Knot, an impossibly complex tangle that had defeated all who attempted to unravel it. While others tried to patiently trace each strand, Alexander drew his sword and cut straight through, solving in seconds what had seemed unsolvable for years.

In software engineering, we often face our own Gordian Knots — codebases so tightly coupled that untangling them step by step feels impossible. The conventional wisdom tells us to refactor incrementally, to carefully trace dependencies, to be patient. But sometimes, the most effective solution is to take Alexander’s approach: make a clean cut, isolate what you need, and start fresh.

That’s the story of how we modularized Komoot’s Android codebase.

Introduction

When I joined Komoot, I inherited a codebase that many Android developers would find familiar: a monolithic module that had grown organically over years of development. While the team had extracted some utility libraries along the way, the vast majority of the application logic lived in a single, massive, crazy huge :komoot module.

This architectural constraint became especially painful when we faced an exciting challenge: building Atlas, a completely new search tool using Jetpack Compose. The idea of developing a modern, declarative UI within our existing monolith was almost impossible. Compose Preview was essentially unusable — the compilation times were so long that the rapid iteration cycle Compose promises simply wasn’t possible.

In addition, working in the monolithic module had become slow and frustrating. Every small change triggered lengthy build times and developers couldn’t work on features in isolation.

We knew that before we could build Atlas effectively, we needed to restructure our codebase. Modularization wasn’t just a nice-to-have; it was a prerequisite for moving forward.

The Theoretical Foundation

Before diving into the technical work, we needed to understand our options. Android modularization generally follows two main approaches, and the industry best practice combines both:

Modularization by layer organizes code by technical responsibility — data, domain, and presentation layers. This creates clear boundaries between different types of logic but can lead to feature code being scattered across multiple modules.

Modularization by feature organizes code around user-facing capabilities. Each feature becomes a self-contained module that can be developed, tested, and even deployed independently. This approach aligns better with how teams are often organized and how users think about applications.

The hybrid approach, which we adopted, combines both strategies. We organized the codebase into four main layers:

- Application layer:

:app-*— Thin modules containing only application-level concerns like navigation wiring and dependency injection setup - Feature layer:

:feat-*— Business logic and UI for specific user-facing features - Data layer:

:data-*— Repositories, data sources, and models - Utility layer:

:lib-*,:core-*,:common-*— Shared UI components, network clients, analytics, and other cross-cutting concerns

However, understanding the theory was just the beginning. We had to acknowledge and embrace a fundamental truth: modularization is not a one-time project — it’s an ongoing process and a shift in team mindset. You can’t modularize a large codebase in a sprint or even a quarter. It requires patience, incremental progress, and team buy-in. Our initial goal wasn’t to modularize everything, but to establish the patterns and infrastructure that would make continuous modularization possible.

Planning and Execution

The God Object Problem

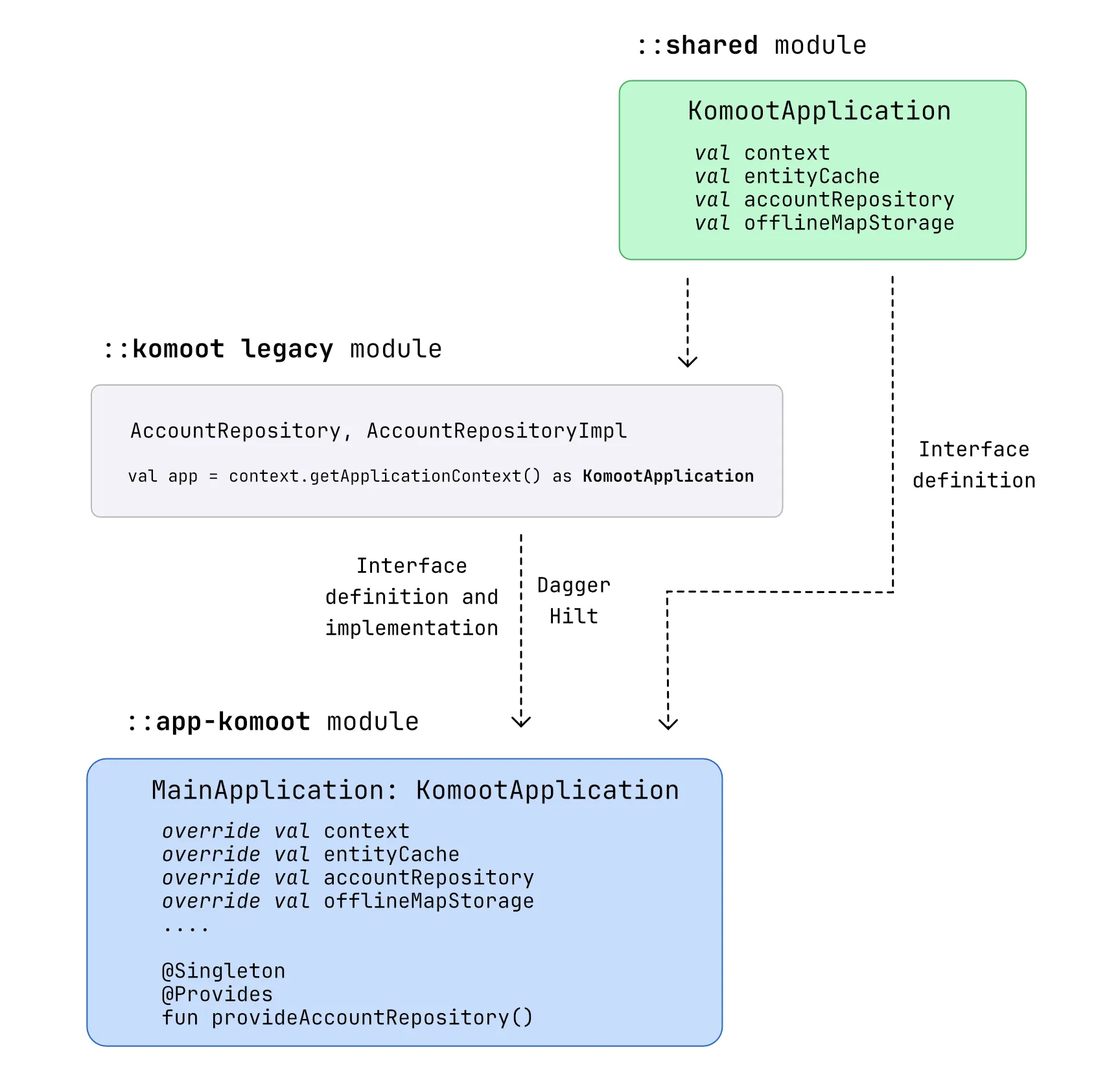

Our biggest obstacle was the Application class — a God object that had evolved into a service locator containing references to virtually every system in the app: network clients, database instances, analytics trackers, and dozens of other dependencies. Activities and fragments throughout the codebase reached up to this application instance to get whatever they needed.

This created a circular dependency problem: to modularize features, we needed to break dependencies on the monolithic module, but the Application class itself was deeply embedded in that monolith.

Breaking the Monolith

Our solution was surgical but effective:

-

Create an interface for the Application class: We extracted

KomootApplicationas an interface containing only the essential services that the legacy code needed to access. This interface went into a new shared module. -

Split the monolith: We created a new

:app-komootmodule containing only the Android application entry point, and the implementation ofKomootApplication. The massive:komootmodule remained as “legacy” but now received the application context through the interface rather than directly accessing theApplicationclass. -

Migrate to Hilt: With the structure in place, we gradually introduced Hilt for dependency injection. This was crucial for allowing new modules to declare their dependencies without reaching up through the God object pattern.

-

Build the first feature module: The

:feat-atlasmodule was created at the same level as:komoot, not nested within it. This was psychologically important — it meant that new features would be first-class citizens, not subordinate to the legacy code. -

Create supporting infrastructure: We added

:core-ui-composefor shared Compose components,:core-app-navigationfor a simple navigation abstraction, and:data-*modules for the data layer. Each module was kept focused and prevented from becoming another monolith. -

We rested :)

Solving Multi-Module Navigation

One of the trickiest problems was navigation. How do you navigate from the legacy monolith to a new feature module, or between feature modules, without creating tight coupling?

We created a simple navigation interface in the :core-app-navigation module. The :app-komoot module provides the implementation that knows how to navigate to all features. Individual feature modules only depend on the navigation interface and call methods like appNav.openAtlas() without knowing anything about how Atlas is implemented or where it lives in the module graph.

While we considered navigation frameworks like Jetpack Navigation or Voyager, we deliberately kept this simple. Modularization was already a significant undertaking — adding a new navigation paradigm at the same time would have been too much complexity at once.

Gradle Build Files Migration

As part of the modernization effort, we converted 53% of our Gradle build files from Groovy to Kotlin DSL. This wasn’t just about using a more modern syntax — Kotlin DSL provides type safety, better IDE support, and makes it easier to extract common build logic. This laid the groundwork for creating reusable configuration plugins that would make future module creation faster.

Developer Experience Improvements

We created Gradle commands to streamline module creation, reducing the ceremony of adding new modules and ensuring consistency across the codebase.

Benchmarking and Results

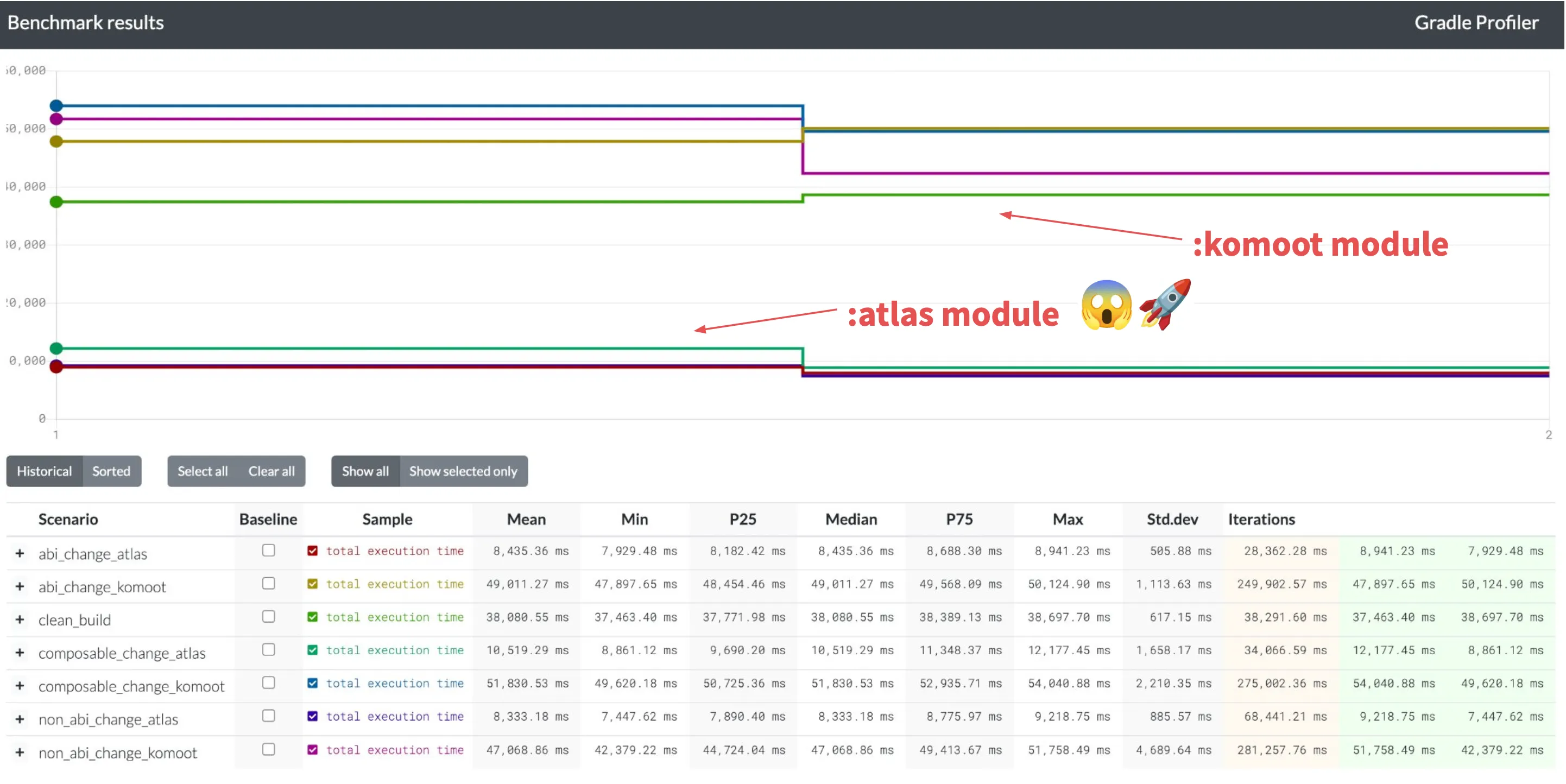

We didn’t want to rely on subjective feelings about whether modularization was working. We needed data.

The Benchmarking Plan

Using Gradle Profiler, we established baseline measurements on the master branch before any modularization work. We measured several scenarios:

- ABI changes: Modifications that change a module’s public interface, forcing dependent modules to recompile

- Non-ABI changes: Internal changes that don’t affect the module’s interface

- Compose changes: UI modifications in Compose files

- Clean builds: Full recompilation from scratch

We then ran the same benchmarks on the OKR branch containing our modularization work, focusing on comparing the legacy :komoot module with the new :feat-atlas module.

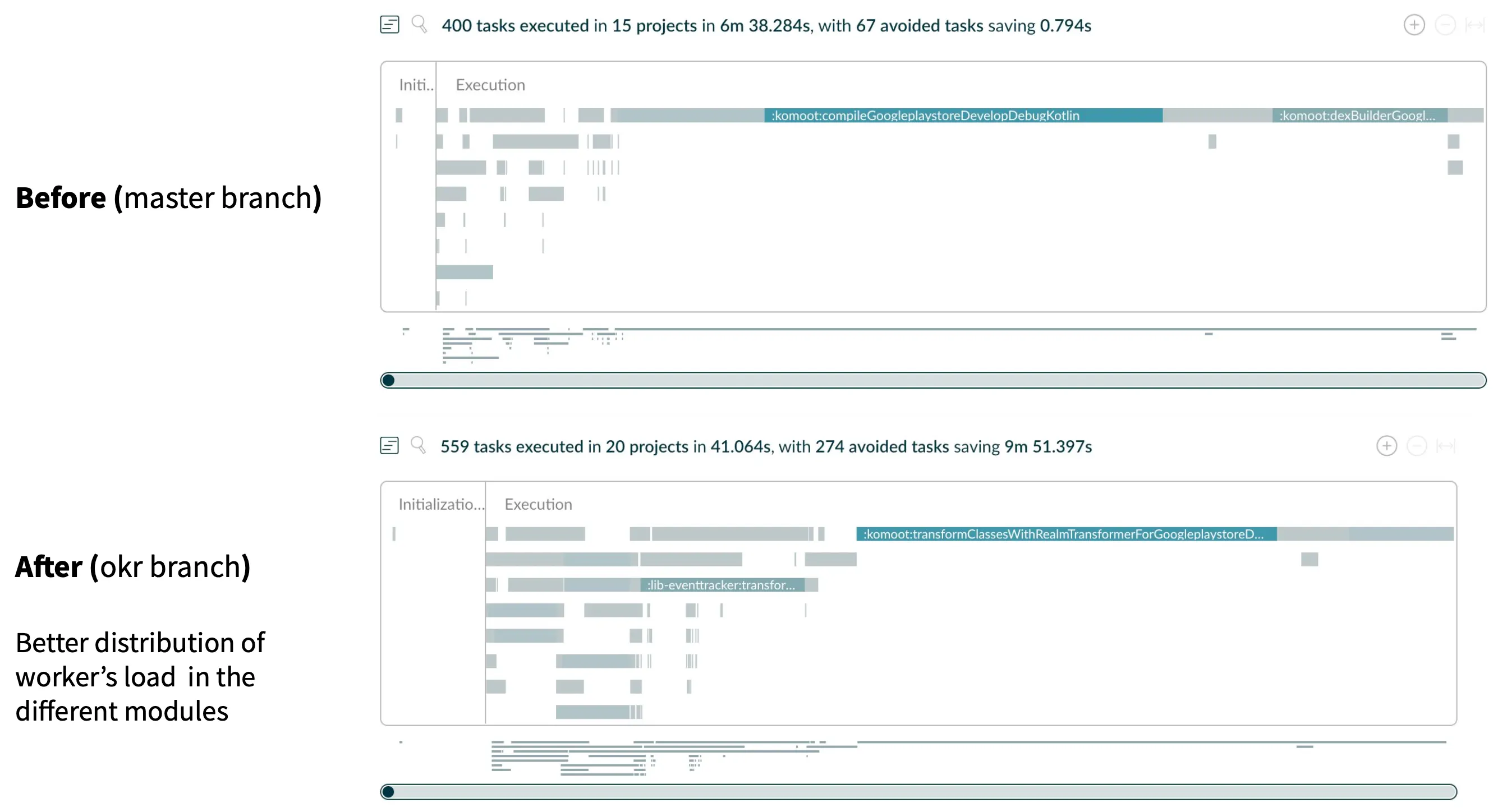

Gradle Enterprise Scans

Before and after Gradle scans revealed dramatic improvements:

- Build cache effectiveness improved from 16.8% to 49% cached tasks. While some of this was likely due to a Gradle wrapper update, the modular structure made caching far more effective.

- Parallelization became significantly more effective. The task execution timeline showed much better distribution of work across CPU cores.

The Numbers

The results exceeded our expectations:

Build times for :feat-atlas were 7x faster than for :komoot across all scenarios. This wasn’t a marginal improvement — it was transformational.

- ABI changes: Atlas ~8.4s vs Komoot ~49s

- Non-ABI changes: Atlas ~8.3s vs Komoot ~47s

- Compose changes: Atlas ~10.5s vs Komoot ~51.8s

All tests in the Atlas module completed in under 9 seconds, including Compose changes. Critically, the Atlas module already contained complex functionality. These weren’t artificially simple benchmarks. The performance gains were real and sustainable.

Team Learnings

Modularization changed how our team thinks about code organization:

-

Start small, establish patterns: We didn’t try to modularize everything at once. We built one excellent example (Atlas) that demonstrated the benefits and established patterns for others to follow.

-

Isolation enables velocity: Feature teams can now work independently without stepping on each other’s toes. When you’re working in

:feat-atlas, you don’t care what’s happening in the legacy module. -

The mental model shift is real: Initially, some developers found the module boundaries restrictive. Over time, these boundaries became liberating — they reduce cognitive load and make the impact radius of changes predictable.

-

Build time improvements compound: Faster builds mean more iteration cycles, more experiments, more refactoring. The productivity gains are larger than the raw numbers suggest.

-

Quality over speed: We focused on doing modularization right rather than fast. Taking time to establish proper navigation abstractions and dependency injection patterns paid dividends as we added more modules.

Conclusion

Transforming Komoot’s Android codebase from a monolith to a modular architecture wasn’t just a technical achievement — it fundamentally changed how we develop software. Features that seemed impossibly complex to add now have clear homes. Tools like Compose Preview that were theoretically available but practically unusable now work as advertised.

If you’re facing similar challenges with a monolithic Android codebase, I hope our experience helps. Start small, establish patterns, measure obsessively, and commit to the long-term journey. Modularization isn’t a sprint — it’s a transformation of how your team builds software.

To Iwo, who created Atlas together with me, and the entire Komoot Android team who embraced this change: thank you! :)

Links

- Android at Scale — Droidcon

- A complete journey of Android modularization

- Forging the path from monolith to multimodule app

- Improve Android productivity

- Speeding up your Android Gradle builds (Google I/O ’17)

- Getting started with feature modularization in Android Apps

- The Pitfalls of Preliminary Over-Modularization in Android Projects